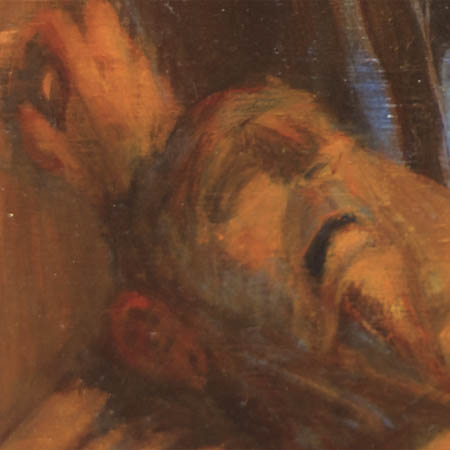

Prayer Desk

oil on desk, 30″ x 20″ x 26″, 2020

I think of the painting as a merging of time-space. And multiple types of existence: the Velasquez and the infinite lemons, the life-cycle represented by the three figures at left, the hand reaching for the door knob at the end of life, the unmanned boat heading to the sunset.

Velasquez is painting lemons, but to me the composition is about the egg. The egg is the compostional device that holds these worlds together. It is the basis of Northern composition (as opposed to the Hambidge’s Greek golden section).

I call it Prayer Desk, because middle age is looking beyond his reality of death for justice to set things right in his world.

I thought of this as a reset. I remembered Sonia Schniebolk encouraging, my drawing on my desk in her Algebra class – to the point of having it removed from the base, varnished and hung on her classroom wall. And here I am at middle age, trying my hand at it again.

ArtsWorcester displayed Prayer Desk in its One Show October-November, 2020, below

Eggs on Hambidge’s Face

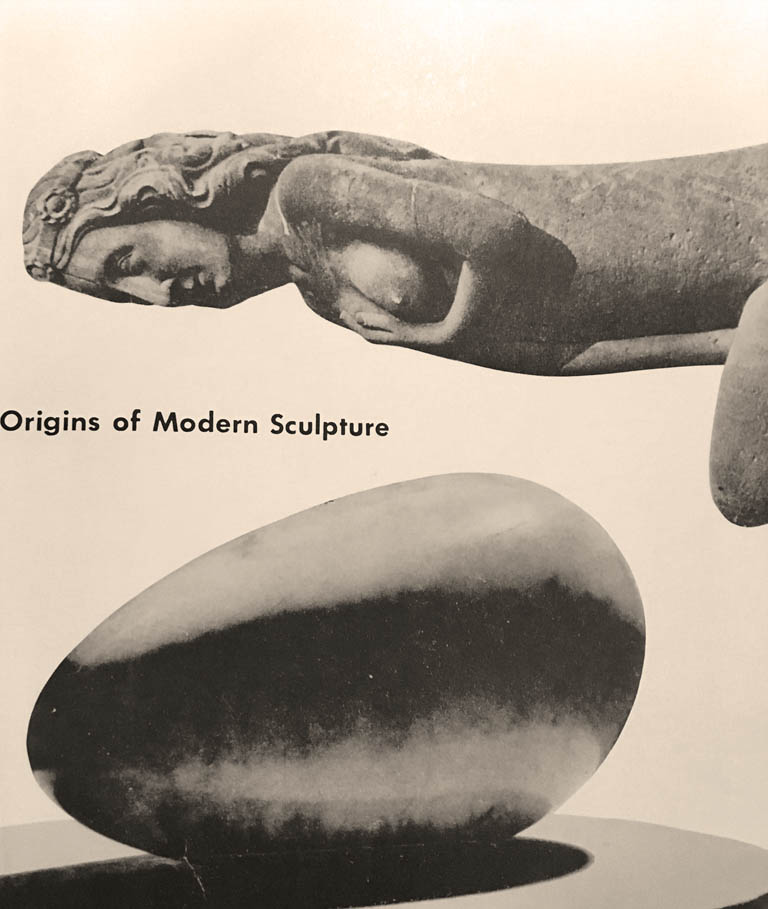

Jay Hambidge begins his 1926 geometric-deconstruction-of-art book, The Elements of Dynamic Symmetry, by writing that Greek geometry-composition is “immeasurably superior to the … Saracenic, Mahomedan, Chinese, Japanese, Persian, Hindu, Assyrian, Coptic, Byzantine and Gothic” method.

I was taught Hambidge’s methodology — or rather a simplified derivative (the book is 132 pages and complex).

Come to find out there are other legitimate ways of constructing pictures, including using the ovoid, egg-form as a compositional device. I encountered this in Leo Bronstein’s El Greco. In that book he describes El Greco as a bit of a crossroads figure ingesting and processing both Renaissance Mannerism and Byzantine egg-like compositional structure:

the infusion of Asiatic ornamental tradition [in] Byzantium transformed the classical [i.e. Greco-Roman] pattern into a more complex configuration, more varied in plastic expression — a configuration that we might classify as elliptical, or (having to do with the building of volume in pictorial space) as ovoid -Leo Bronstein, El Greco, 1950

I like El Greco. And Byzantine and Asian art. These latter two are what Bronstein describes as Northern. By Northern he’s referring to the giant swath of land from the Middle East to Germany, Eastern Europe, England, Ireland to Persia, India, China and Japan. As opposed to Southern, which means Egyptian, Nubian (as recent research suggests), Greek, Roman, and resultantly, the whole Western world in which we live.

Paul Rand’s thoughts about the egg

When you start with a portrait and search for a pure form, a clear volume, through successive eliminations, you arrive inevitably at the egg. Likewise, starting with the egg and following the same process in reverse, one finishes with the portrait. -Pablo Picasso, L’Intransigeant, Paris, 15 Juin, 1932

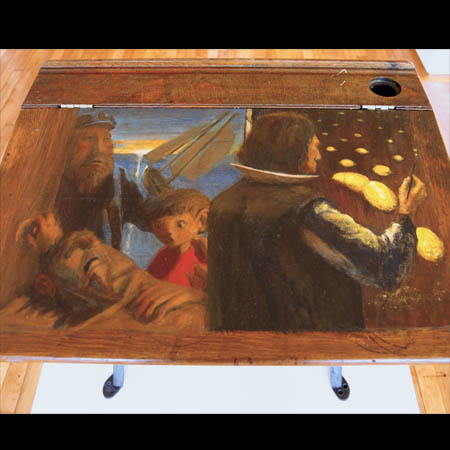

Below is a composition in which you can see the eggs in action — to help define the space-volume.

Might as well mention a couple of other things I do, that I can see in this beginning: my paintings often emerge from the swirls and strokes of my imprimatura. Like a Rorschach, what I see and choose to bring to light can’t help but reveal what’s important to me. I got the idea from Leonardo’s advice to see what you can see in a broken plaster wall. Also, it’s kind of a triptych in a single panel, based on the Dura-Europos precedents, like the Ezekiel dry-bones to their angelic restoration to someone’s beheading. In the Prayer Desk, I’m using a similar approach. Last, I’ve been making my pictures lately in antique frames. I think the first time I did this was when a painter friend gave me an antique map frame into which I built my Angel painting of 2005. I saw the evidence of someone else painting in a frame in a museum in a work by an Impressionist, but I can’t remember who — there were paint daps, drips and splotches on the inner edge of the frame. Working this way helps me find a tone for the image. It seems to me to put my pictures sometime else in history. I’m always after that sense of “always was” inevitability in my work, and the frame feels a challenge in that regard. It also lets me build the image into a complete art object, not just a planar picture. And I think the last thing about the frame is that it feels consonant with the Dura-Europos paintings that always incorporated decorative borders and panels with their figurative work.